What this Cincinnati park teaches us about racial equality

- Samantha Pryor

- Jun 12, 2020

- 3 min read

This morning I was feeling particularly adventurous.

I decided to venture beyond my tried and true walking path and treat myself to a quick stroll in Cincinnati's renowned International Friendship Park.

The 22-acre park sits just east of downtown Cincinnati, hugging the Ohio River. The park's long and narrow paths make it desirable by locals who seek an easy and shaded route for walking, running or biking.

To the naked eye, the park is a spectacular display of sculptures, vistas and foliage; however, to the beholder who dares to dig deeper -- studying the colorful plaques and subtle pavement details -- the park reveals itself as a dedication to a man prided on the principles of universal acceptance and community.

That man was Theodore M. Berry, Cincinnati's first African-American Mayor.

It wasn't until my escapade today that I was truly struck by the significance of Ted Berry. As I paused to take it all in, I escaped the 21st century and flew back in time to November 5, 1904, the year Berry was born in Maysville, Kentucky.

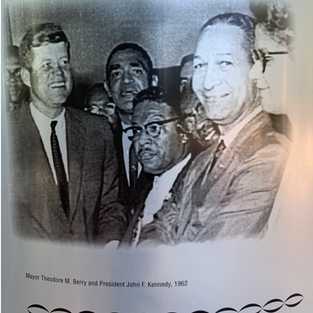

I felt relieved pondering the photos delicately displayed on the park's monuments, which celebrated Berry as a young boy, with his community and even alongside President John F. Kennedy.

I couldn't help but feel as if this new-found knowledge was a sign, especially with today's racial injustice felt by everyone, including a nine-year old boy who has begun protesting at home.

But for a moment I paused and focused on the park's mantra of international peace and friendship.

Why Ted Berry?

Berry seemed like a standup guy. The Cincinnati History Library and Archives share that despite being born into poverty, he garnered a national reputation as a leader in the Civil Rights movement. A couple noteworthy things about Berry:

1924: As a college senior, he was the first African-American class valedictorian in Cincinnati. He was also the first black assistant prosecuting attorney for Hamilton County.

1947: He was appointed to serve on the NAACP Ohio Committee for Civil Rights Legislation, where he helped create Urban League of Greater Cincinnati -- a program dedicated to improving social and economic life for segregated African-Americans.

1957: Berry ran for Mayor of Cincinnati and lost due to a new system of proportional representation, in which voters listed candidates in order of preference (often disqualifying minority candidates).

1965: After his defeat, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Berry to head the Office of Economic Opportunity’s Community Action Programs, where Berry helped create programs that would offer various services to low-income individuals and families. (More about Cincinnati's group here.)

1972: Berry was elected as mayor of Cincinnati and served for four years. He is remembered for his advocacy for poor communities and underrepresented individuals.

''I believe mayors should consult with all groups -- the poor, labor, business and so on,'' he said in an interview in 1965. ''You don't get representation by exercising paternalistic determination.''

Everything Berry represented is rooted at Friendship Park

Clearly Berry was very important in the equal representation movement, and Friendship Park doesn't skimp when driving home the idea of inclusivity.

The park's design reflects themes and stories that use art and nature to honor, celebrate and reconnect people and cultures.

The gardens represent the five continents and are laid out in a way that portrays connectedness despite cultural differences. The design and plant materials of each continent also vary slightly to celebrate differences of people and places.

The two intertwining paths symbolize a friendship bracelet, encouraging people to meet as paths cross. The pathways also are symbolic of the interdependence between man and nature and are shaped like DNA strands! If you pay close attention, you will find embedded symbols in the concrete representing culture and nature.

During my walk home, I couldn't help but think about what Berry would say if he was still alive today. As I came up short, I instead turned my attention to all the people, full of joy, walking and conversing in the park on this beautiful sunny day. Closing my eyes, I reflected on how lucky we were that this park was built, and that Berry existed to make it stand for something far greater than ourselves.

Although we may not always have the answers, we have a space to reflect and pray, to feel connected and at home. And at the end of the day, isn't that what parks are for? A place for us to realize that despite our racial differences, backgrounds and viewpoints, we can come together -- as people -- to make sense of this world together.

Comments